Astronomer kortlægger formen på en supernovas gennembrud — og den er ikke sfærisk

I en banebrydende observation med Very Large Telescope (VLT) i Chile har astronomer indfanget de allerførste øjeblikke af en massiv stjernes eksplosion. Resultatet? Supernovaens såkaldte “gennembrud” — den indledende chokbølge, idet eksplosionen bryder gennem stjernens overflade — var aflang og ikke perfekt kugleformet, hvilket udfordrer årtier gamle antagelser.

Hændelsen, der har fået betegnelsen SN 2024ggi, indtraf, da en stjerne med omkring 12–15 gange Solens masse nåede slutningen af sit liv. Blot 26 timer efter, at det første lys fra eksplosionen blev registreret, rettede VLT-forskere deres instrumenter mod objektet og indsamlede data, som afslørede en ujævn, klumpet form på eksplosionens front.

Hvorfor det er vigtigt:

Tidligere er supernovaeksplosioner — især den tidlige gennembrudsfase — i modeller blevet betragtet som nogenlunde sfæriske. Denne opdagelse tvinger astrofysikere til at gentænke, hvordan stjerner eksploderer, hvordan energien spredes, og hvordan dannelsen og fordelingen af grundstoffer foregår i disse første kaotiske øjeblikke.

Hvad sker der nu:

Det videnskabelige hold håber at kunne observere fremtidige supernovaer endnu tidligere, så det bliver muligt at lave 3D-kortlægning af eksplosionernes former. Disse indsigter kan forfine forudsigende supernovamodeller og forbedre vores forståelse af, hvordan tunge grundstoffer spredes i kosmos.

At the beginning of the end of a star’s life, its core runs out of hydrogen to convert into helium. The energy produced by fusion creates pressure inside the star that balances gravity’s tendency to pull matter together, so the core starts to collapse. But squeezing the core also increases its temperature and pressure, making the star slowly puff up. However, the details of the late stages of the star’s death depend strongly on its mass.

A low-mass star’s atmosphere will keep expanding until it becomes a subgiant or giant star while fusion converts helium into carbon in the core. (This will be the fate of our Sun, in several billion years.) Some giants become unstable and pulsate, periodically inflating and ejecting some of their atmospheres. Eventually, all the star’s outer layers blow away, creating an expanding cloud of dust and gas called a planetary nebula.

All that’s left of the star is its core, now called a white dwarf, a roughly Earth-sized stellar cinder that gradually cools over billions of years.

A high-mass star goes further. Fusion converts carbon into heavier elements like oxygen, neon, and magnesium, which will become future fuel for the core. For the largest stars, this chain continues until silicon fuses into iron. These processes produce energy that keeps the core from collapsing, but each new fuel buys it less and less time. The whole process takes just a few million years. By the time silicon fuses into iron, the star runs out of fuel in a matter of days. The next step would be fusing iron into some heavier element but doing so requires energy instead of releasing it.

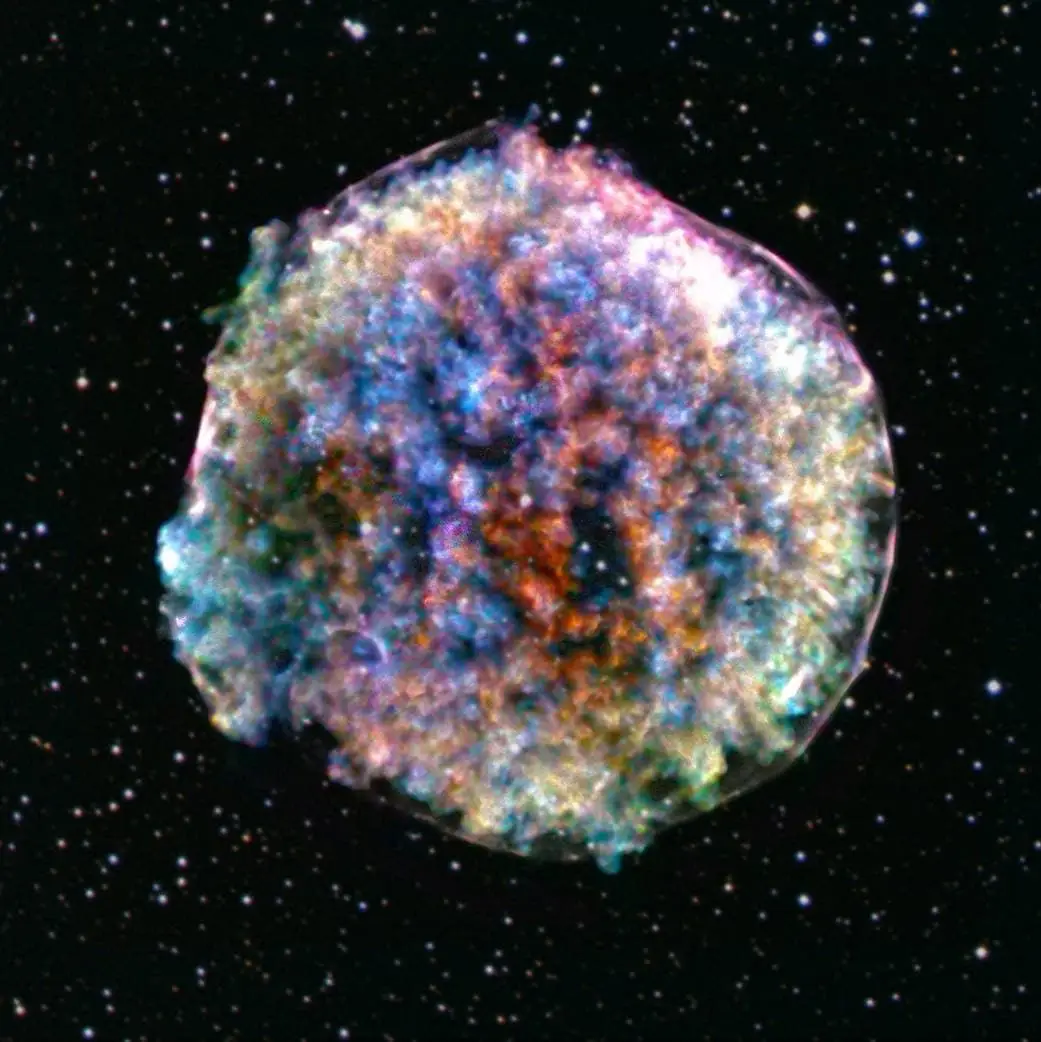

The star’s iron core collapses until forces between the nuclei push the brakes, then it rebounds. This change creates a shock wave that travels outward through the star. The result is a huge explosion called a supernova. The core survives as an incredibly dense remnant, either a neutron star or a black hole.

Material cast into the cosmos by supernovae and other stellar events will enrich future molecular clouds and become incorporated into the next generation of stars.

Source: science.nasa.gov